by Brad Chrisman

As an experienced pediatric rehab physician, Kerstin Sobus, M.D., knows that there are no quick remedies for children learning to cope with disabilities. Often, success is measured in small steps.

“I talk to parents about what’s it going to take to make your kid as independent as possible so they’re ready for kindergarten, then middle school, then high school and so on,” the Indianapolis-based doctor says. “That’s how I look at it. You just have to do what you can do.”

Likewise, in her role as a volunteer on numerous trips to Haiti, Sobus has found that improving the quality of medical care on the Caribbean island can be a slow, deliberate process. But the key to long-term, sustained success, she believes, is helping local medical providers become as independent and self-sufficient as possible.

And in both places – environments as worlds-apart as Indiana and Haiti – she frequently turns to Global HELP as a source for free, high-quality, relevant information.

Sobus says she first learned about Global HELP a several years ago when she was attending a medical conference on cerebral palsy. A colleague showed Sobus the organization’s comprehensive, illustrated book The HELP Guide To Cerebral Palsy, and she was immediately impressed.

“I was like, ‘Whoa, this is really good!’ That was the first time I realized it was available. It was really informative.”

Sobus, who has participated in several medical-mission trips to Haiti through an organization called Nehemiah Vision Ministries (NVM), immediately thought of the nurses who worked at the group’s clinic in Chambrun, a village located about 20 kilometers outside Port Au Prince.

“We had two nurses that were staying there year-round, and that CP book was very helpful,” she says. “That was just a really great book.”

“And then the next year a bunch of us were talking about what else was online and I found out that, wow, we have the Ponseti method available!” she says, referring to Clubfoot: Ponseti Management, the popular Global HELP publication that has been translated into 30 languages, including Creole, the first language of most Haitians.

“I said, ‘I need that, because we don’t have access to good information on serial casting,'” she says. “And the next time I was in Haiti, in walks a mother with a baby, umbilical cord still attached, with clubfeet. I said, ‘I’ve got what you girls need. I can download you something on Ponseti casting.'”

“So it’s been really helpful for the nurses that are down there in the trenches to have information,” Sobus says. “It just made it really easy for them to have information right at their fingertips.”

On a human scale, the 7.0 magnitude earthquake that struck Haiti on Jan. 12, 2010, was one of the most punishing natural disasters in recorded history. It’s estimated that at least 220,000 people died and more than 300,000 were injured. Already cited as the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, Haiti found itself at the center of a massive relief effort.

When Sobus, who had been making trips to Haiti since 2007, first heard the devastating news, she knew right away that she wanted to put her skills to use.

“I got down there the second week,” she says. “It was chaotic, with medical teams from all over the world, but there was a good system in place for how they were triaging patients and everything.”

Over the ensuing five years, as the humanitarian effort evolved from the initial response to the need for long-term solutions, Sobus says it became increasingly clear that the key to sustainable progress will be helping Haiti’s medical community become self-sufficient. Her organization, NVM, has been careful about plans to expand its clinic and open a hospital.

“We always had a clinic, and the clinic got bigger, and then it got bigger. But we decided not to make the hospital go as fast because we didn’t think we were ready to do that,” she says. “That’s because we wanted it to be Haitian-run, and we thought if we moved it forward too fast, we wouldn’t have a Haitian-run team ready to do it. And we always wanted it to be Haitian-run.”

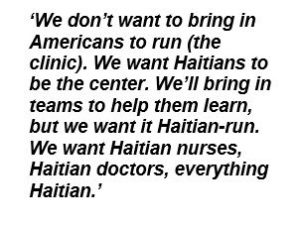

“We don’t want to bring in Americans to run it,” Sobus says. “We want Haitians to be the center. We’ll bring in teams to help them learn, but we want it Haitian-run. We want Haitian nurses, Haitian doctors, everything Haitian.”

Global HELP, she says, has been an important part of that endeavor.

“Some of (the Global HELP information) that I’ve had them download, we leave it for the Haitian doctors that are there, and that’s been really helpful,” she says. “Once that the nurses knew that it was there, then they would download for the physicians.”

Back home in Indianapolis, Sobus says that Global HELP materials have been especially useful in working with immigrant populations.

“In Indy, it’s amazing how many refugees we have,” she says. “I have some really good OTs (occupational therapists) who do serial casting and things, and every once in a while they get a patient and they say, ‘I’m sorry, I just don’t speak this language, and I don’t know how to help them.'”

“I say, ‘Remember, we have this really nice global system with all this information. They have the Ponseti method, they have things for cerebral palsy, they have things for spina bifida.’ Lo and behold, we’ll find what we want in a certain language.”

“Some of the refugees come from very educated families. Others don’t read,” Sobus says. “But it’s written in such a way that the translators can read it to them in their own language, and their eyes just light up.”

We’re grateful for our audience’s positive feedback. To contribute your own story, please feel free to contact us at questions@global-help.org